There's always a great temptation, when dealing with theories, to try and fit the world neatly into them. Anyone who's stumbled onto a system and found it useful has experienced this; once you start thinking in terms of Meyers-Briggs personality types, or Ayurvedic doshas, or whatever framework you're into, the tendency is to apply them to everything. Heck, it's fun, and it can be illuminating up to a point. But ultimately, the theory never fits completely. It's the old map and territory conundrum: to make a good enough map to really represent the lay of the land, we'd have to make it as big as the landscape we're mapping. And that would be awkward. And expensive. Not very travel-friendly.

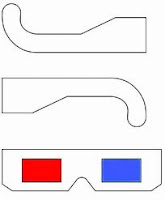

The systems of Chinese Medicine are many and subtle; there's yin-yang, the Five Elements (or, more accurately, Five Phases), the Six Conformations, and our topic of the moment, the 12 Organs or organ networks. Twelve is a pretty big number when it comes to a system. Twelve tones are enough for to generate all of Western music. (And five enough for most of blues and rock.) Twelve makes for a pretty fine-grained map. But it's still a map. So how to bend a linear, finite sort of system like the one at hand around an complex, infinite universe? Clearly, for starters, one-to-one correspondences won't do. That way we'd run out of symbols way before we ran out of things to map them onto. One solution is to do something akin to what music does: multiple notes at a time. Shadings, crescendos, trills, arpeggios. Skillful combinations of the basic building blocks. A wise, skillful classical medicine certainly must use its theories this way, with flexibility and artfulness. Okay. But there's still an issue of evoking something complex and alive using seemingly static symbols. What my current Cosmology teacher Gregory Sax suggest--and I paraphrase very loosely here--is a sort of 3-D glasses effect. Red alone isn't enough; nor is blue, but by their interaction they give rise to a third dimension, and the picture pops off the page. It's the motion between contradictory elements that produces a third, fundamentally different phenomenon and brings the whole picture to life.

This has all been a very long-winded way of justifying the simultaneous-X-and-Y nature of the Lung. Which we haven't even begun discussing. Yikes. But here goes. Here's Story X.

As a metal organ in the Five Element classification, the Lung has to do with contraction, going inward, sinking down, cutting away. Its emotion is grief, the pain we must feel in order to release our attachments and sink down to the lowest place (the Water phase), whence we will be able to rise again (Wood). Its symbol is the tiger: the mythological White Tiger that represents the Fall. And like that season of falling leaves, the lung moves down: it is called the "upper source of water," for it sits at the top of the thorax like a lid and condenses the steam gleaned from the Heart-Kidney axis and distributes this usable 'fresh water' form of qi down and outward. As Metal is dry, so the Lung is susceptible to dryness and must be kept appropriately moist. When the lung dries up, so does bodily nourishment and vitality; tuberculosis is a classic Lung pathology. The spirit associated with the Lung is the Po, which unlike the Liver's wandering Hun stays in the body. Like a tiger, Po has strong animal instincts and provided a connection to the earth. Indeed, it is understood that after death the Po will sink back down into the ground.

Now this little story may sound like utter Greek to some, but to those familiar with Chinese medical theory it ought to be reasonably convincing: Metal, upper source of water, the Po--all the key talking points of the Lung. Now let's have a look at the other side. Here's Story Y:

Within the calendrical framework, the Lung holds the year's first position. The Chinese year traditionally began in very early Spring, and this is the month associated with the Lung. The Gallbladder saw the subtle but powerful re-introduction of yang at the Winter solstice; the Liver continued the uphill journey back towards summer, and now the Lung takes the third and decisive step. The yang energy is now as prevalent as the yin, and momentum is on yang's side. All of nature is taking a breath and expanding: springtime. Motion is upward and outward. This is a moist time of year, what with the snowmelt, and the Lung is susceptible to this moisture. Too damp and it quickly develops phlegmy congestion (isn't this how we tend to get sick?) And as for the tiger, what better symbol for the fierceness and explosive power of the new yang of springtime...

And so forth. For the average TCM student, this story, Story Y, may be less familiar. But it's no less true to the symbols of Chinese cosmology; the Lung position is definitely the first month of Spring. There's undeniably a Wood aspect to the Lung as well as a Metal one. And Metal and Wood are opposites. It's tempting to give in to frustration and walk away from the whole project, concluding that 'it just goes to show these symbols can be stretched to mean just about anything.' But before you join this camp, at least try on the fancy colored glasses. With one eye on Metal and the other on Wood--one on X and the other on Y--a new perspective leaps off the page. Call it Story Z:

The Lung has one foot in Metal, the other in Wood; it has a dual nature like the scales of Libra (the Western astrological sign that corresponds most closely to the Lung's month). Its hexagram reveals this duality: It features three yang lines below three yin lines; heaven below earth. Heaven wants to float up, earth to sink down, so this hexagram, called Tai, is a picture of a merging union. But in the process of merging, these upward and downward forces create pressure between them. This is the origin of the Lung's ability to "pressurize" the system and keep our vessels full of qi. Therefore when the Lung is weak, our energy flags and we lose vitality. A weak voice is a classic sign of Lung qi deficiency; there is not enough pressure in the system to power the vocal output. This Lung pressure is born of a delicate balance between forces, and indeed the Lung is called the "delicate organ" because it demands balance. Too damp or too dry and it suffers. And the Lung's association with Spring is not actually about bursting forth; that will happen next month with the Large Intestine. For now, yang has merely reached equilibrium with yin. Yang cannot yet erupt visibly; the Lung's month of early spring is the time when the stage is set, the spring coiled, the system pressurized. It's all potential energy, not yet actualized into kinetic motion. The tiger--the crouching tiger of martial arts fame--symbolizes this: he's poised to pounce. The Lung's poise, dynamic nature and proximity to the Heart make it uniquely well suited to its 12 Officials cabinet position of Prime Minister, the director of the other organs. Everyone is willing to listen to someone so highly placed, well balanced, inspired and full of life.

The Lung has one foot in Metal, the other in Wood; it has a dual nature like the scales of Libra (the Western astrological sign that corresponds most closely to the Lung's month). Its hexagram reveals this duality: It features three yang lines below three yin lines; heaven below earth. Heaven wants to float up, earth to sink down, so this hexagram, called Tai, is a picture of a merging union. But in the process of merging, these upward and downward forces create pressure between them. This is the origin of the Lung's ability to "pressurize" the system and keep our vessels full of qi. Therefore when the Lung is weak, our energy flags and we lose vitality. A weak voice is a classic sign of Lung qi deficiency; there is not enough pressure in the system to power the vocal output. This Lung pressure is born of a delicate balance between forces, and indeed the Lung is called the "delicate organ" because it demands balance. Too damp or too dry and it suffers. And the Lung's association with Spring is not actually about bursting forth; that will happen next month with the Large Intestine. For now, yang has merely reached equilibrium with yin. Yang cannot yet erupt visibly; the Lung's month of early spring is the time when the stage is set, the spring coiled, the system pressurized. It's all potential energy, not yet actualized into kinetic motion. The tiger--the crouching tiger of martial arts fame--symbolizes this: he's poised to pounce. The Lung's poise, dynamic nature and proximity to the Heart make it uniquely well suited to its 12 Officials cabinet position of Prime Minister, the director of the other organs. Everyone is willing to listen to someone so highly placed, well balanced, inspired and full of life. And with such a beautiful coat. Did I mention the Lung rules the surface of the body?

Next time on Chinese Organ Networks: the power of the rising sun, the manifestation of the grossly physical, and the Large Intestine.

No comments:

Post a Comment