Today on the bus I saw a woman with a stroller get on and take a seat near the front. She took out a bag of jelly worms and ate one, then fed another of the chewy red and yellow tubes to her infant. I couldn’t see his or her little face, but I could picture the baby sucking the candy right down like a fat strand of spaghetti. Ah, I thought--sweetness. It’s the primordial taste, a direct link to our animal brains, the message that says “nourishment.” But before someone gets on my case for advocating a diet of Haribo gummy candies for newborns, there’s a distinction that ought to be made. There’s sweet, and then there’s sweet.

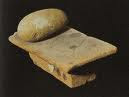

As hunter-gatherers and early agriculturalists--in other words, people who got along somehow without food-processing technology much more sophisticated than the blade, the mortar and pestle, and the clay cooking/fermenting vessel, humans evolved to recognize viable sources of nourishment by taste. Basically, the things that tasted good to us were the things that would keep us going, providing strength and nourishment to keep us not just alive but thriving. Things like animal parts (especially internal organs like liver and heart, which are typically prized by traditional cultures and are eaten first by wild animals), seeds and grains, starchy roots and tubers, fruit and nuts. Most of these foods taste sweet, in subtle or not-so-subtle ways. Take bread, for instance: chewed for more than a few seconds, the starches in any loaf break down into shorter-chain carbohydrates, i.e. sugars. So, in the mythical golden age of human nutrition, when the only problem with most people’s diets was that they might not be getting enough to keep body and soul together, sweetness was a pretty good indicator of nutritional value. Enter the industrial revolution, slave labor, factory farming, and the McDonald’s-ization of global food trends, and the picture gets pretty distorted. Now sweetness can be extracted from its nutrient matrix and concentrated, packaged and sold. And by golly the stuff is a hit. Rather like crack is a hit. The same can be done with fattiness and saltiness, two other once-reliable indicators of nutrient-density. The result? The ketchup-dipped french fry, which to our taste buds is the perfect combination of fat, salt, and sugar. Unfortunately, 99.999% of the fries out there are made with bad fat (chemical gobbledygook with names like ‘partially hydrogenated cottonseed oil’) bad salt (refined NaCl, possibly iodized but stripped of all other trace minerals), and even bad sugar (high-fructose corn syrup, which manages to be even sweeter and more problematic than the old devil, regular old white sucrose). The potatoes are from a sterile, mineral-depleted lunar wasteland fumigated by spacesuit-wearing farmers, and the tomatoes, well, aw hell, they can count as a vegetable!

As hunter-gatherers and early agriculturalists--in other words, people who got along somehow without food-processing technology much more sophisticated than the blade, the mortar and pestle, and the clay cooking/fermenting vessel, humans evolved to recognize viable sources of nourishment by taste. Basically, the things that tasted good to us were the things that would keep us going, providing strength and nourishment to keep us not just alive but thriving. Things like animal parts (especially internal organs like liver and heart, which are typically prized by traditional cultures and are eaten first by wild animals), seeds and grains, starchy roots and tubers, fruit and nuts. Most of these foods taste sweet, in subtle or not-so-subtle ways. Take bread, for instance: chewed for more than a few seconds, the starches in any loaf break down into shorter-chain carbohydrates, i.e. sugars. So, in the mythical golden age of human nutrition, when the only problem with most people’s diets was that they might not be getting enough to keep body and soul together, sweetness was a pretty good indicator of nutritional value. Enter the industrial revolution, slave labor, factory farming, and the McDonald’s-ization of global food trends, and the picture gets pretty distorted. Now sweetness can be extracted from its nutrient matrix and concentrated, packaged and sold. And by golly the stuff is a hit. Rather like crack is a hit. The same can be done with fattiness and saltiness, two other once-reliable indicators of nutrient-density. The result? The ketchup-dipped french fry, which to our taste buds is the perfect combination of fat, salt, and sugar. Unfortunately, 99.999% of the fries out there are made with bad fat (chemical gobbledygook with names like ‘partially hydrogenated cottonseed oil’) bad salt (refined NaCl, possibly iodized but stripped of all other trace minerals), and even bad sugar (high-fructose corn syrup, which manages to be even sweeter and more problematic than the old devil, regular old white sucrose). The potatoes are from a sterile, mineral-depleted lunar wasteland fumigated by spacesuit-wearing farmers, and the tomatoes, well, aw hell, they can count as a vegetable! I tend to get a little carried away when I think about what our society eats. But it’s not my fault--things really are that unbalanced. I’m not really one for statistics, but I’d be willing to bet that the average American is at least five times more likely to know how to drive a car and upload a digital photo than how to cook a simple meal of beans, greens, and grains from scratch. And once quotidian food preparation techniques like making sourdough bread or fermenting a crock of kraut are practically obsolete in mainstream America. There’s a lot more that can be said on the subject of our “national eating disorder,” as Michael Pollan puts it, but as that wasn’t really meant to be my focus in this post I’ll refer interested readers to his by-now seminal The Omnivore’s Dilemma instead. My contribution here is this: people should eat real (ideally, local, seasonal) food in appropriate quantities, yes. But what if that’s not enough?

Most of the people I see in my capacity as an Ayurvedic/herbal health consultant have something in common. They are craving nourishment. I don’t mean that they are wasting away, suffering from calorie-deficiency, but they find that they’re not as satisfied by their food as they would like, or they feel a nameless hunger for something beyond what they’re getting. This hunger has spiritual dimensions as well, of course--the hunger for meaning that typifies the postmodern era--but I’m talking about the physical plane. Perhaps its simply the people I attract--I, as someone who has struggled with issues of nourishment and who envision my work in this world as an act of nourishing, broadly-defined; maybe it’s the spectacles I wear that see everything in a nutrition-tinted hue--but I don’t think that’s all of it. Across the nation and the world, people are hungry.

As I learned to see from Ayurvedic teacher Claudia Welch, how many Americans are weighed down with weight that doesn’t really belong to them, sheer ballast that’s standing in for true nourishment? Eating nutritionally empty foods can lead easily to a vicious cycle of hunger for nutrients, a hunger which is then fed with more junk, which creates weight but leads to ever more ravenous hunger...even for those who eat a reasonably balanced, mostly whole-foods diet, there is the same craving for grounding.

Grounding: this mysterious-sounding idea bridges the gap between physical and non, and ties in another symptom of post-modernity: we live too much in our heads. Our lack of nourishment is inseparable from our lack of sensitivity to our bodies, and to the earth. It might be said--I’ll say it--that we hunger, at root, for connection, for the umbilical cord linking us to the great mama underfoot. “Alternative medicine” abounds in ways to talk about this: the root chakra, the earth element, sacral vibrations...these ways of conceptualizing all share an association with the lower parts of the body. Maybe what we lack, on some collective level, is the ability to shake our metaphysical booty. (This isn’t so far-fetched: health would be a lot more marketable if people realized the connection between it and their libido.)

So what to do about it? I haven’t even mentioned the myriad stresses we’re subject to, from traffic jams to conference calls and jet lag, environmental toxins, you name it. From an herbalist’s point of view, luckily, these issues and those of grounding and nourishment all point to a common set of remedies. For nourishing, for grounding, for cooling our feverish appetites, for building our reserves and stabilizing our frayed nerves, sweet roots are what the order of the day. My staunchest allies, the herbs I find myself reaching for more than any other for myself and other people, belong to this class of nourishing, adaptogenic roots: Ashwagandha. Shatavari/Asian asparagus species. American Ginseng. Licorice. These can be taken as powder or tea or even tincture, but my favorite way is simply to eat them, gnawing on the tough Ashwagandha, chewing the sweet Asparagus rhizomes like gummy candy, sucking and chewing up a slice of licorice root until the sweetness is gone. All extremely safe herbs (the only contraindication for any of these is with licorice, which due to its watery nature shouldn’t be used in cases of water retention or hypertension), they can be chewed freely. I’ve even been known to give a Christmas present of a jar of “nourishing roots to gnaw” to a certain family member who, I was reminded, loves to do just that.

To these grounding, building, soothing roots, I like to add some more specifically nervine herbs, especially in cases of heavier stress or where there is more heat and irritation (Pitta involvement). With my Ayurvedic background, Gotu Kola (Centella asiatica) and Shankhapushpi (Convolvulus alsinoides) are my go-tos, but more recently I’ve been discovering the deeply cooling, calming, tension-relaxing nature of Motherwort and the nerve-feeding capacity of Oatstraw and seed. A nice Ayurvedic trick is to add some calcium-rich bhasma (calcined mineral) preparation such as prawal or muktasukti bhasma, coral or oyster shell ash. Given conservation issues, I go with oyster shell. It lends a grounding weight to a formula and is especially nice for the Vata/Pitta conditions that so many people seem to be struggling with, and it isn’t expensive. Finally, in cases where some extra grounding (bordering on mild sedation, such as in anxiety with insomnia) is in order, I will use something along the lines of Valerian root. I prefer not to give heavy, dulling herbs for long periods, but they can be indispensably useful in the short-term.

Nourishing roots: Dong Quai (Chinese Angelica), Asian licorice, Ashwagandha, Tien Moon Dong (Asian Asparagus rhizome), American Ginseng

While herbs can nourish us and supplement the problematic food sources that are unavoidable, they are no substitute for deeper grounding work. Depending on who, what, when and where you are, this might mean digging in a garden bed, sitting quietly and doing nothing for ten minutes, going for a walk in the woods, or playing soccer. It almost certainly means unplugging yourself from the cyberworld for a spell. In the spirit of practicing what I preach, I’m off to cook some dinner.